History

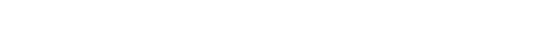

The Murphy Branch of the Western North Carolina Railroad delivered thousands of mountaineers from the wilderness of their landlocked hills. A year after iron rails reached Asheville in 1880, workers scattered to the west of the city, digging, filling, and blasting an extension of the line that stretched 116 miles to Murphy, providing thousands with a path to reach the outside world.

The iron horse beat riding a wagon, but in many ways the young railroad was still primitive. In 1892, a visitor from Chicago described it as “little more than two streaks of rust and a right-of-way.” With tongue in cheek, he told the Chicago Tribune, “when the wind is just right, the fastest train on the line, the ‘Asheville Cannon Ball,’ can make 10 miles an hour.”

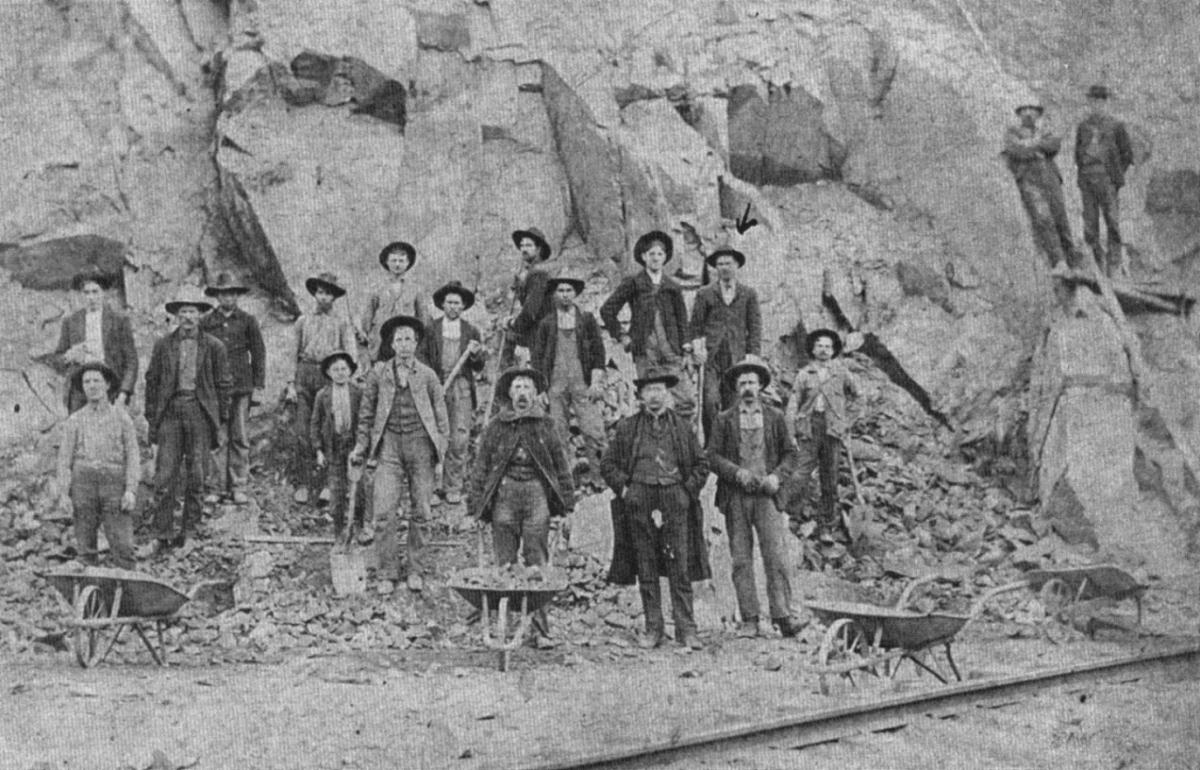

Rails changed the way of life for Western North Carolina residents. Mercantile business was commodities for a few of the bare necessities. Conveniences and luxuries were not even dreamed of and cash was hard to come by. The iron rails brought a flood of salesmen who peddled oil lamps that superceded tallow candles and New England “factory cloth” to replace scratchy, uncomfortable homespun. From door to door they sold books, pump organs, enlarged pictures, jewelry, lightning rods, baubles and doodads.

Passenger business was so good by the turn of the 20th century that six passenger trains ran every day between Asheville and Lake Junaluska and four daily between Asheville and Murphy. It was not easy to cut this branch line through the mountains. If it had not been for the practical, self-educated engineer Capt. J. W. Wilson, a rigidly honest and industrious man, it might not have been accomplished for years. One of Capt. Wilson’s most challenging tasks was the grade on the west side of the Balsams that was steep and curvy, with gaping ravines. His second obstacle was the 836-foot Cowee Tunnel through a shaky mountain west of Dillsboro. High iron topped the Balsam Mountains at 3,100 feet, at the time the highest elevation of any railroad in the Eastern United States.

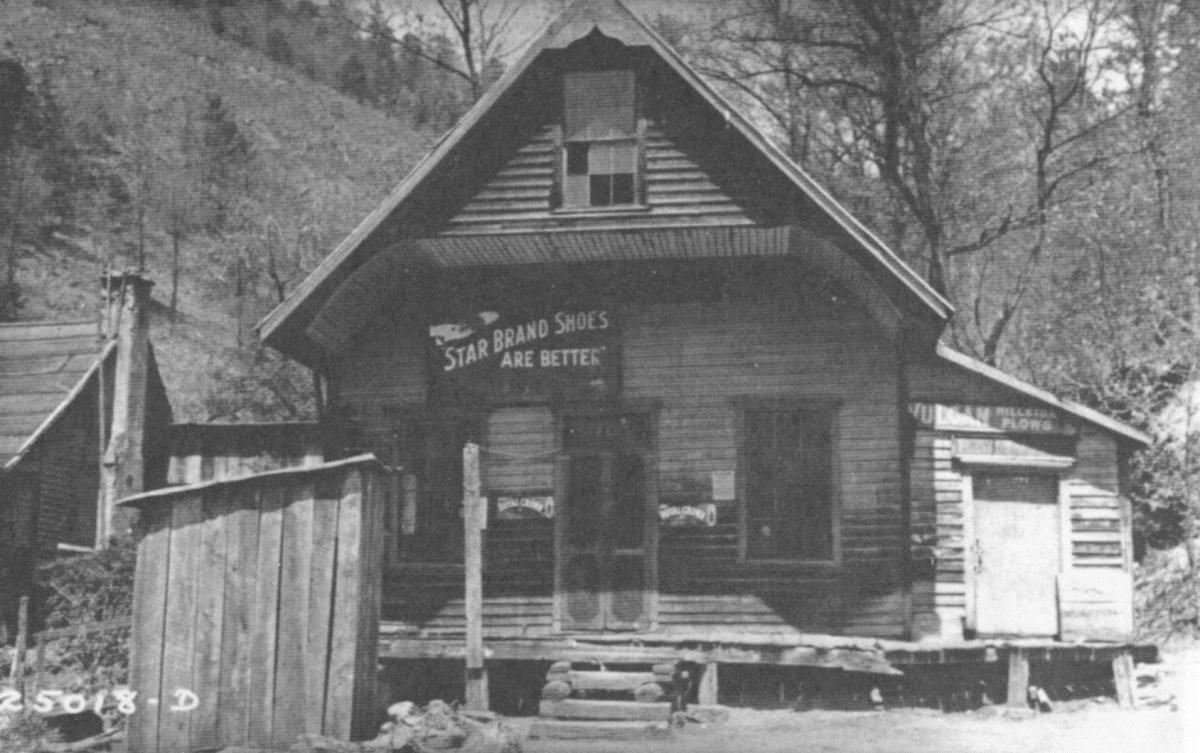

The railroad was built by convicts working under the gun. In one of the most chilling accidents during construction, 19 inmates drowned in the Tuckasegee River at the mouth of the tunnel. Crossing the river to work, the raft carrying the iron-shackled convicts capsized and all aboard, except for guard Fleet Foster and convict Anderson Drake, died in the waters. Foster was rescued by Drake, who stole the guard’s wallet while pulling him to shore. When the wallet was found in Drake’s duffel, he was whipped and put to work in the tunnel at hard labor instead of receiving a hero’s honor. Those who died were buried in unmarked graves on top of a small hill near the mouth of the tunnel.

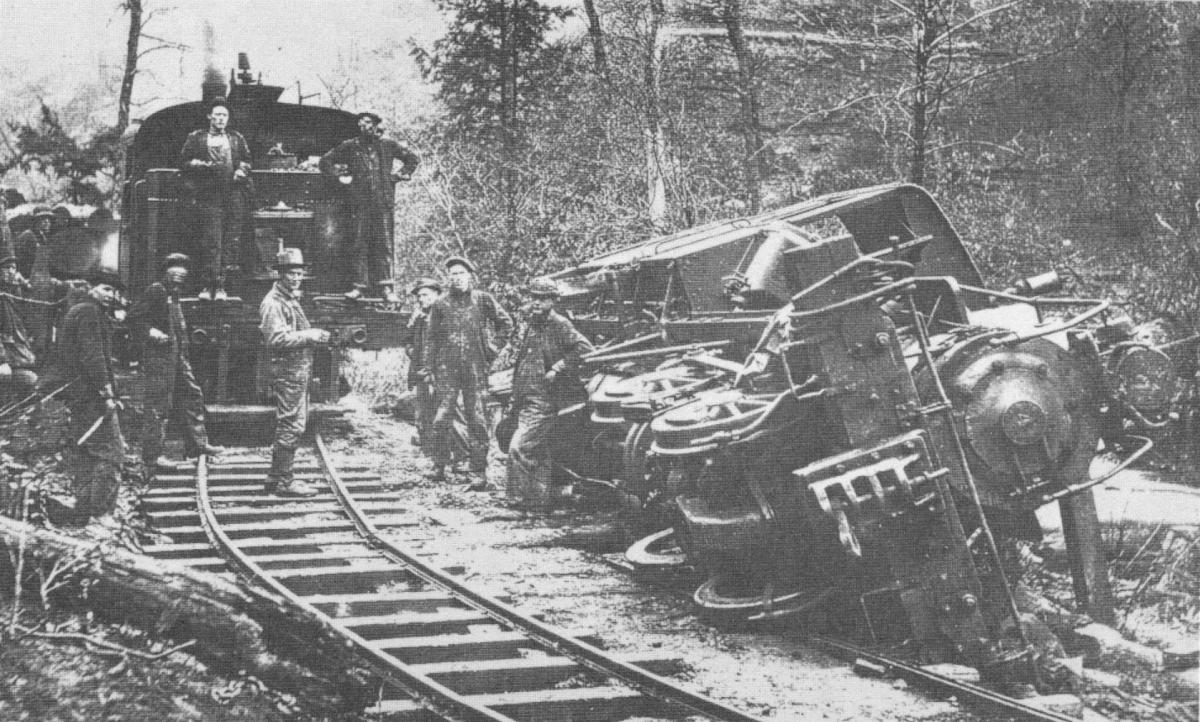

In the early years of the 20th century, there were a number of runaways on Balsam Mountain and a couple of wrecks inside Cowee Tunnel and in the river, but loss of life was small. As improvements were made to the railroad, accidents declined. The Murphy Branch experienced its heaviest use during wartime, in the early 1940s when the massive Fontana Dam was constructed. Thousands of carloads of cement, equipment, and other materials reached the construction site by rail on a spur line built from Bushnell to Fontana. Huge shipments of copper ore from mines in the western end of North Carolina and Copperhill, Tennessee, increased the line’s tonnage. In the 1920s, ribbons of concrete crawled through the mountains, linking towns together.

With the increasing popularity of the automobile, passenger traffic on the Murphy Branch, then owned by the sprawling Southern Railway System, began to decline. Southern discontinued all passenger traffic on the Murphy Branch on July 16th, 1948, ending 64 years of service that had opened Western North Carolina to the outside world. When freight traffic dropped off by 1985, Norfolk Southern closed the Andrews to Murphy leg of the Murphy Branch and the State of North Carolina purchased the Dillsboro to Murphy tracks to keep them from being destroyed.

By 1988, many entities had come together to form the Great Smoky Mountains Railway, which then began running passenger excursions. Rolling stock for the GSMR was purchased from various railroads around the nation. The Dillsboro to Nantahala route was one of the most scenic on the Murphy Branch and the excursion trains caught on right away. Upward of 200,000 passengers enjoy the scenery and the experience of a true operational railroad each year aboard passegner excursion trains. American Heritage Railways purchased the GSMR in December of 1999. The Great Smoky Mountains Railway operates today as the newly organized Great Smoky Mountains Railroad.